Cladus: Eukaryota

Supergroup: Opisthokonta

Regnum: Animalia

Subregnum: Eumetazoa

Cladus: Bilateria

Cladus: Nephrozoa

Cladus: Deuterostomia

Phylum: Chordata

Subphylum: Vertebrata

Infraphylum: Gnathostomata

Superclassis: Tetrapoda

Classis: Mammalia

Subclassis: Theria

Infraclassis: Placentalia

Ordo: Primates

Subordo: Haplorrhini

Infraordo: Simiiformes

Parvordo: Catarrhini

Superfamilia: Cercopithecoidea

Familia: Cercopithecidae

Subfamilia: Cercopithecinae

Tribus: Papionini

Genus: Papio

Species: Papio hamadryas

Name

Papio hamadryas, (Linnaeus, 1758)

Vernacular names

Internationalization

English: Hamadryas Baboon

עברית: בבון מצרים

日本語: マントヒヒ

Polski: Pawian płaszczowy

Türkçe: Habeş maymunu

Papio hamadryas, Papio hamadryas, Papio hamadryas,

References

* Papio hamadryas on Mammal Species of the World.

Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference, 2 Volume Set edited by Don E. Wilson, DeeAnn M. Reeder

-------

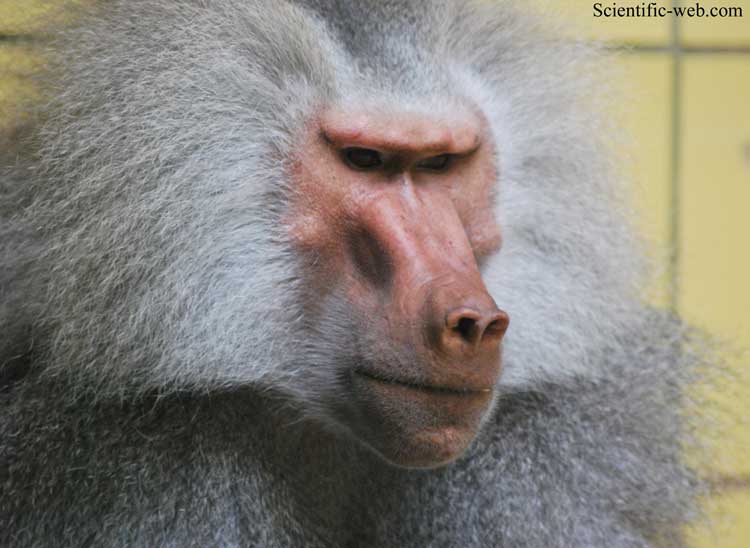

The Hamadryas Baboon (Papio hamadryas) is a baboon from the Old World monkey family. It is the northernmost of all the baboons; its range extends from the Red Sea in Egypt to Eritrea, Ethiopia and Somalia. Baboons are also native to and live in Southwestern Arabia, especially in Yemen. The mountains of Yemen and the horn of Africa make it a great place for the baboons live, where predators are not as common as in central Africa. The Hamadryas Baboon was a sacred animal to the ancient Egyptians as the attendant of Thoth, and so, is also called the Sacred Baboon.

Description

Apart from the striking size difference between the sexes (males are often twice as large as females) which is common to all baboons, this species also shows sexual dimorphism in coloration. Males are silver-white colored and have a pronounced cape which they develop around the age of ten, while the females are capeless and brown. Their faces range in color from red to tan to a dark brown that older males often exhibit. Males are an average of 30" tall, with tails about 20" long, and weigh an average of about 45 lbs. Tails end in small tufts. Infants are dark in coloration and lighten after about one year. Hamadryas baboons reach sexual maturity at about 51 mo. for females and between 57 and 81 mo. for males.[3] The average life span of Hamadryas baboons in the wild is about 35 years.

Ecology

The Hamadryas Baboon lives in semi-desert areas, savannas and rocky areas, requiring cliffs for sleeping and possibilities to drink water. The Hamadryas Baboon is omnivorous and is adapted to its relatively dry habitat. It is not discriminating in its search for food, eating grass, roots, seeds, reptiles, insects, small mammals and crops. Hamadryas baboons will dig for water in dry streambeds. Hamadryas baboons are diurnal and have the largest day ranges of any primate.

Behavior

The Hamadryas Baboon is unusual among baboon and macaque species in that its society is strictly patriarchal and patrilineal. Females may try to establish matrilines but they are usually overruled by the males, who forcefully transfer them among social units and away from their female relatives.[4][5] The males limit the movement of the females. They herd them with visual threats and will grab or bite any female that wanders too far away.[6] Males will sometimes raid harems for females, resulting in aggressive fights. Some males succeed in taking a female from another's harem. This is called a 'takeover'.[7][8][9] Visual threats are usually accompanied by these aggressive fights. This would include a quick flashing of the eyelids accompanied by a yawn to show off the teeth. As in many species, infant baboons are taken by the males as hostages during fights.

The baboon has an unusual 4-level social system called a multi-level society. Most social interaction occurs within small groups called one-male units or harems containing one male and up to nine females which the males lead and guard. A harem will typically include a younger "follower" male who may be related to the leader.[10][11][12] Two or more harems unite repeatedly to form clans.[13] Within clans, the dominant males of the units are probably close relatives of one another and have an age related dominance hierarchy.[14][15]

Bands are the next level. Two to four clans form bands of up to 200 individuals which usually travel and sleep as a group.[16][17][18] Both males and females rarely leave their bands. The dominant males will prevent infants and juveniles from interacting with infants and juveniles from other bands. Bands may fight with one another over food, etc and the adult male leaders of the units are usually the combatants.[19][20] Several bands may come together to form a troop. Several bands also often share a cliff-face which they sleep on.[21][22][23]

Reproduction

Like other baboons, the Hamadryas Baboon breeds aseasonally. The dominant male of a one-male unit does most of the mating, though other males may occasionally sneak in copulations as well [24] [25] [26][27]. Often, a male forms a harem by "adopting" subadult females and teaching them to follow him. He protects them and in 1–2 years, they go into estrus and he mates with them.

Females do most of the parenting. They nurse and groom the infant and it is not uncommon for one female in a unit to groom an infant that is not hers. Like all baboons, Hamadryas baboons are intrigued by their infants and give much attention to them. Dominant male baboons prevent other males from coming into close contact with their infants. They also protect the young from predators. The dominant male tolerates the young and will carry and play with them [28]. When a new male takes over a female, she may go into deceptive estrous cycles. This behavior is likely an adaptation that functions to prevent the new male from killing the offspring of the previous male.

Human interaction

Hamadryas baboons are often depicted in ancient Egyptian art as the sacred attendants of Thoth, scribe to the gods. Occasionally Thoth also appears in the form of a hamadryas (often depicted carrying the moon on his head), as an alternative to his usual depiction as an ibis-headed figure. Hapi, one of the Four Sons of Horus that guarded the organs of the deceased, is hamadryas-headed and thus often sculpted as the lid of a canopic jar. Hamadryas baboons were revered because certain behaviors that they perform were seen as worshiping the sun, and they were viewed as mediators between humans and the gods.

Transformation of field and pastureland represents the main threat of the Hamadryas Baboon, their natural enemies (the leopard and the lion) having been nearly exterminated in their range. The IUCN lists it as "least concern" in 2008.[2]

References

1. ^ Groves, C. (2005). Wilson, D. E., & Reeder, D. M. ed. Mammal Species of the World (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 166-167. ISBN 0-801-88221-4. http://www.bucknell.edu/msw3/browse.asp?id=12100586.

2. ^ a b Gippoliti, S. & Ehardt, T. (2008). Papio hamadryas. In: IUCN 2008. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Downloaded on 4 January 2009.

3. ^ Rowe, Noel. The Pictorial Guide to Living Primates, Pogonias Press (Charlestown, Rhode Island: 1996)

4. ^ Sigg and Stolba et al. 1982

5. ^ Swedell 2002

6. ^ Swedell and Schreier 2009

7. ^ Swedell and Tesfaye 2003

8. ^ Swedell 2006

9. ^ Swedell and Schreier 2009

10. ^ Kummer, 1968

11. ^ Stammbach, 1987

12. ^ Swedell 2006

13. ^ Schreier and Swedell 2009

14. ^ Abegglen, 1984

15. ^ Sigg and Stolba et al. 1982

16. ^ Kummer, 1968

17. ^ Abegglen, 1984

18. ^ Swedell 2006

19. ^ Kummer, 1968

20. ^ Stammbach, 1987

21. ^ Kummer, 1968

22. ^ Abegglen, 1984

23. ^ Swedell 2006

24. ^ Kummer, 1968

25. ^ Sigg and Stolba et al. 1982

26. ^ Stammbach, 1987

27. ^ Swedell and Saunders 2006

28. ^ Kummer, 1968

General Sources

* Kummer, H. 1968. Social Organisation of Hamdryas Baboons. A Field Study. Basel and Chicago: Karger, and University Press.

* Sigg, H, Stolba, A, Abegglen, J. -J. and Dasser, V. 1982. Life history of hamadryas baboons: Physical development, infant mortality, reproductive parameters and family relationships. Primates, 23(4): 473-487.

* Abegglen J. J. 1984,. On Socialization in Hamadryas Baboons. Blackwell University Press.

* Stammbach, E. 1987. Desert, forest, and mountain baboons: Multilevel societies. Pp. 112-120 in B. Smuts, D. Cheney, R. Seyfarth, R. Wrangham.

* Swedell L (2002). Affiliation among females in wild hamadryas baboons (Papio hamadryas hamadryas). International Journal of Primatology 23: 1205-1226.

* Swedell L, Tesfaye T (2003). Infant Mortality After Takeovers in Wild Ethiopian Hamadryas Baboons. American Journal of Primatology 60: 113-118.

* Swedell, L. 2006. Strategies of Sex and Survival in Hamadryas Baboons: Through a Female Lens. Pearson Prentice Hall.

* Swedell L, Saunders J (2006). Infant Mortality, Paternity Certainty, and Female Reproductive Strategies in Hamadryas Baboons. In Reproduction and Fitness in Baboons: Behavioral, Ecological, and Life History Perspectives (Swedell L, Leigh SR, eds), pp 19-51. New York, Springer.

* Schreier A, Swedell L (2009). The Fourth Level of Social Structure in a Multi-Level Society: Ecological and Social Functions of Clans in Hamadryas Baboons. American Journal of Primatology 71: 1-8.

* Swedell L, Schreier A (2009). Male aggression towards females in hamadryas baboons: Conditioning, coercion, and control. In Sexual Coercion in Primates and Humans: An Evolutionary Perspective on Male Aggression Against Females (Muller MN, Wrangham RW, eds), pp 244-268. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press.