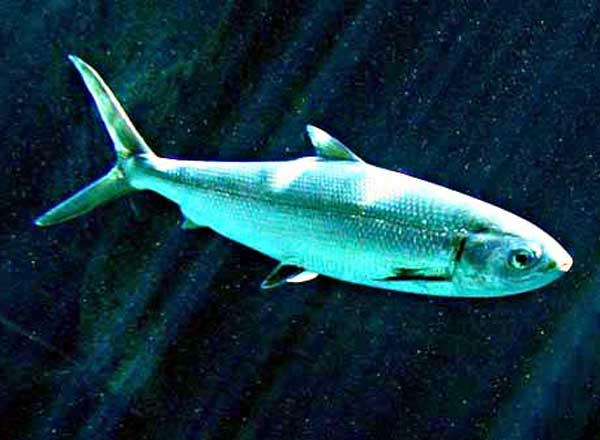

Chanos chanos Cladus: Eukaryota The milkfish (Chanos chanos) is the sole living species in the family Chanidae. (About seven extinct species in five additional genera have been reported.)

Milkfish have a generally symmetrical and streamlined appearance, with a sizable forked caudal fin. They can grow to 1.70 meters (6 ft) meters but are most often about 1 metre (39 in) in length. They have no teeth and generally feed on algae and invertebrates. They occur in the Indian Ocean and across the Pacific Ocean, tending to school around coasts and islands with reefs. The young fry live at sea for two to three weeks and then migrate to mangrove swamps, estuaries, and sometimes lakes and return to sea to mature sexually and reproduce. Aquaculture The milkfish is an important seafood in Southeast Asia and some Pacific Islands. Because milkfish is notorious for being much bonier than other food fish, deboned milkfish, or "boneless bangus," has become popular in stores and markets. History Milkfish aquaculture first occurred around 800 years ago in the Philippines and spread in Indonesia, Taiwan and into the Pacific.[1] Traditional milkfish aquaculture relied upon restocking ponds by collecting wild fry. This led to a wide range of variability in quality and quantity between seasons and regions.[1] In the late seventies, farmers first successfully spawned breeding fish. However, they were hard to obtain and produced unreliable egg viability.[2] In 1980 the first spontaneously spawning happened in sea cages. These eggs were found to be sufficient to generate a constant supply for farms.[2] Farming methods Fry are raised in either sea cages, large saline ponds (Philippines) or concrete tanks (Indonesia, Taiwan).[1] Milkfish reach sexual maturity at 1.5kg, which takes 5 years in floating sea cages, but 8-10 years in ponds and tanks. Once 6 kilograms (13 lb) is reached (8 years) an average of 3-4 million eggs will be produced each breeding cycle.[1] This is mainly done using natural environmental cues. However, there have been attempts using gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogue (GnRH-A) to induce spawning.[3] Some still use the traditional wild stock method. This involves capturing wild fry using nets.[1] Milkfish hatcheries, like most hatcheries, contain a variety of cultures, as well as the target species. For example rotifers, green algae and brine shrimp.[1][4] They can either be intensive or semi-intensive.[1] Semi-intensive methods are more profitable with it costing $6.67 US per 1000 fry in 1998, compared with $27.40 per 1000 fry for intensive methods.[4] However, the experience required by labour for semi-intensive hatcheries is higher than intensive.[4] Milkfish nurseries in Taiwan are highly commercial and have densities of about 2000/litre.[5] Indonesia achieves similar densities but has more backyard-type nurseries.[5] The + have integrated nurseries with grow-out facilities and have densities of about 1000/litre.[5] There are three methods of outgrowing: pond culture, pen culture and cage culture. * Shallow ponds are found mainly in Indonesia and the Philippines. These are shallow 30–40 centimetres (12–16 in), brackish ponds with benthic algae, usually used as feed.[1] They are usually excavated from ‘nipa’ or mangrove areas and produce ~ 800kg/ha/yr. Deep ponds (2-3m) have a more stable environment and began in 1970. They so far have shown less susceptibility to disease than shallow ponds.[5] Most food supply is natural food (known as ‘lab-lab’) or a combination of phytoplankton and macroalgae.[1][6] Traditionally this was made on site; food is now made commercially to order.[1] Harvest occurs when the individuals are between 20-40cm (250-500g). Partial harvests remove uniform sized individuals with seine nets or gill nets. Total harvest removes all individuals and leads to a variety of sizes. Forced harvest happens when there is an environmental problem, such as depleted oxygen due to algal blooms and all stock is removed. Possible parasites include parasitic nematodes, copepods, protozoa and helminths.[1] Many of these are treatable with chemicals and antibiotics. Processing and marketing Milikfish processing takes two forms. Traditional ways include smoking, drying and fermenting. Bottling, canning and freezing are of recent origin.[1] There has been a steady increase in demand since 1950.[1] In 2005, 595,000 tonnes was harvested worth USD $616 million.[1] There is an increasing trend toward value-added products.[1] In recent years the possibility of using milkfish juveniles as bait for tuna long lining has started to be investigated, opening up new markets for fry hatcheries.[7] References

Notes 1. ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q http://www.fao.org/fishery/culturedspecies/Chanos_chanos/en

Source: Wikipedia, Wikispecies: All text is available under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License |

|