- Cassini mission page - Iapetus

- The Planetary Society: Iapetus

- Thunderbolts.info Picture of the day article on Iapetus

- Did Iapetus Consume One of Saturn's Rings?

- Hoagland's extremely long, detailed, thorough and off-beat artificial world theory

- mirror matter Iapetus? Z.K. Silagadze's article from Acta Physica Polonica B

|

|

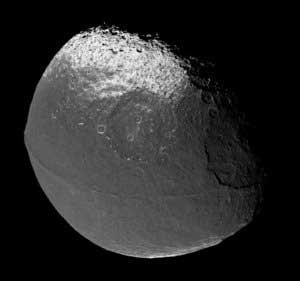

Iapetus (eye-ap'-i-tus, Greek Ιαπετός) (British spelling: "Japetus") is the third-largest moon of Saturn (see: Saturn's natural satellites), discovered by Giovanni Domenico Cassini in 1671. Iapetus is best known for its dramatic 'two-tone' coloration, but recent discoveries by the Cassini-Huygens mission have revealed several other unusual physical characteristics. These mysteries are currently under investigation by scientists and new information about Iapetus is accumulating continuously.

Name Iapetus is named after the mythological Iapetus. It is also designated Saturn VIII. Giovanni Cassini named the four moons he discovered (Tethys, Dione, Rhea and Iapetus) Lodicea Sidera ("the stars of Louis") to honour king Louis XIV. However, astronomers fell into the habit of referring to them and Titan as Saturn I through Saturn V. Once Mimas and Enceladus were discovered, in 1789, the numbering scheme was extended to Saturn VII. The names of all seven satellites of Saturn then known come from John Herschel (son of William Herschel, discoverer of Mimas and Enceladus) in his 1847 publication Results of Astronomical Observations made at the Cape of Good Hope ([2]), wherein he suggested the names of the Titans, sisters and brothers of Cronos (the Greek Saturn), be used.

Orbit The orbit of Iapetus is somewhat unusual. Although it is one of Saturn's largest moons, it orbits much farther from Saturn than the next closest major moon, Titan. It has also the most inclined orbital plane of the regular satellites; only the irregular outer satellites like Phoebe have more inclined orbits. The cause of this is unknown. Because of this distant, inclined orbit, Iapetus is the only large moon from which the rings of Saturn would be clearly visible; from the other inner moons, the rings would be edge-on and difficult to see.

Physical characteristics Recent Cassini image of the night hemisphere of Iapetus, illuminated by reflected light from Saturn The low density of Iapetus indicates that it is primarily composed of ice, with only a small amount of rocky materials. Furthermore, the overall shape of Iapetus is neither spherical nor ellipsoid—unusual for a large moon; parts of its globe appear to be squashed flat, and its unique equatorial ridge (see below) is so high that it visibly distorts the moon's shape even when viewed from a distance. Scientists are currently unable to describe Iapetus's shape perfectly as the Cassini probe has not yet imaged its entire surface. [3] Iapetus is a heavily cratered body, and Cassini images have revealed large impact basins in the dark region, at least three of which are over 350 km wide. The largest has a diameter over 500 km; its rim is extremely steep and includes a scarp over 15 km high.

Two-tone coloration In the seventeenth century, Giovanni Cassini observed that he could see Iapetus only on one side of Saturn and not on the other. He drew the conclusion that one side of Iapetus was darker than the other, a conclusion confirmed by images from the Voyager and Cassini spacecraft. The difference in colouring between the two Iapetian hemispheres is striking. The leading hemisphere is dark (albedo .03–.05) with a slight reddish-brown coloring, while its most of the trailing hemisphere and poles is bright (albedo .5-.6, almost as bright as Europa). The pattern of coloration is analogous to a spherical ying-yang symbol. The dark region is named Cassini Regio, and the bright region Roncevaux Terra. The origin of this dark material is not currently known, though several theories have been proposed (see below). Its thickness is also unknown; there are no bright craters present on the dark hemisphere, so if the dark material is thin it must be constantly renewed since otherwise a meteor impact would punch through the layer to reveal brighter underlying material. When NASA's Voyager 2 flew past Iapetus on August 22, 1981 at a relatively distant 966,000 km (600,000 miles), the spacecraft's cameras could make out few details in the area of dark material, but revealed the bright side to be icy and heavily cratered. On December 31, 2004, the Cassini spacecraft passed within 123,000 kilometers/77,000 miles of Iapetus and photographed Cassini Regio at far a higher resolution than Voyager was able, but the mystery surrounding its origin has only deepened. Cassini is scheduled for a much closer approach on September 10, 2007 -- 1,200 kilometers / 800 miles.

Sources from space Close-up of northern pole. The dark material might be formed of organic compounds similar to the substances found in primitive meteorites or on the surfaces of comets; Earth-based observations have shown it to be carbonaceous and it probably includes cyano- compounds such as frozen hydrogen cyanide polymers. An alternate theory was that the dark material originated from another Saturnian moon, Phoebe. It could have been knocked free from the smaller moon's surface by micrometeor impacts and then swept up by Iapetus' leading hemisphere. However, Phoebe's surface has a different color than that of the dark material of Iapetus - indeed it was recently announced that Phoebe's composition is closer to the bright Iapetian hemisphere than the dark one. [4]

Internal sources It is possible that the dark material may have originated from some internal source, perhaps brought to the surface by a combination of meteor impact and cryovolcanism. This theory is supported by the apparent concentration of the material on crater floors. It has been suggested that since Iapetus is far from Saturn and would have avoided much of the heating its other moons received during the formation of the Solar system, Iapetus may have retained methane or ammonia ice in its interior that later erupted to the surface as cryovolcanic lava and was then blackened by solar radiation, charged particles, and cosmic rays. A dark ring of material about 100 kilometers in diameter straddling the border between the leading and trailing hemispheres of Iapetus is suggestive of such vulcanism, resembling structures that have formed on the Moon and on Mars as a result of volcanic material flowing into impact craters with a central peak. Photomosaic of Cassini images taken Dec. 31, 2004, showing the dark Cassini Regio, large craters, and the newly discovered equatorial ridge An alternative internal source may be the evaporation of water ice. Due to its slow rotation, Iapetus has the warmest surface in the Saturnian system (130 K in the dark region) allowing the sublimation of water ice on the surface. After sublimation, the water then freezes back to the surface and re-heats until it reaches a location where it is no longer able to sublimate. The dark areas may be the result of such a process, since the material there lacks water. However, this hypothesis fails to explain why only one hemisphere is dark.

The equatorial ridge A further mystery was discovered when the Cassini spacecraft imaged Iapetus on December 31, 2004, and revealed an equatorial ridge about 20 km wide and 13 km high extending 1300 km through the center of Cassini Regio[5]. Parts of the ridge rise more than 20 km over the surrounding plains. The ridge follows the moon's equator almost perfectly and is confined to Cassini Regio. Some bright mountains near the boundary of Cassini Regio that apparently belong to this ridge were seen in Voyager photos; however, the Voyagers were unable to make out any details in the dark region itself, so the extent of the ridge is only now apparent. The ridge system is heavily cratered indicating that it is ancient.[6] The images are currently being analyzed by scientists and no firm conclusions have yet been announced about the ridge's origin. Most scientists believe that the ridge must be icy material that welled up from beneath the surface and then solidified, but this does not explain why the ridge follows the equator. Alternatively, Paulo C.C. Freire of Arecibo Observatory has proposed that the ridge and Cassini Regio were created when Iapetus grazed the outer edges of Saturn's rings in the distant past. However's Freire's theory requires Iapetus to have been later ejected to its current, distant orbit around Saturn. [7] See also: List of geological features on Iapetus

Speculation that Iapetus is artificial The oddness of Iapetus has occasionally led to speculation that it may be an artificial construction by extraterrestrials. In 1980, Donald Goldsmith and Tobias Owen suggested that the striking bicoloration of Iapetus might be the result of alien modification of a natural object. In 2005, Richard C. Hoagland speculated that Iapetus might be a fully or partially artificially constructed world by an ancient (and likely long-gone) extraterrestrial civilization. His thesis relies on the moon's arguably angular shape (unusual in a moon of Iapetus's size, which ought to be compressed into an approximately spherical or ellipsoid form under pressures generated by its own gravity), the equatorial ridge, and a close examination of surface features. [8] The scientific mainstream considers such ideas fanciful at best.

Iapetus in fiction

Links

... | Hyperion | Iapetus | Kiviuq | ... Saturn's natural satellites

Pan | Daphnis | Atlas | Prometheus | S/2004 S 6 | S/2004 S 4 | S/2004 S 3 | Pandora | Epimetheus and Janus | Mimas | Methone | Pallene | Enceladus | Telesto, Tethys, and Calypso | Polydeuces, Dione, and Helene | Rhea | Titan | Hyperion | Iapetus | Kiviuq | Ijiraq | Phoebe | Paaliaq | Skathi | Albiorix | S/2004 S 11 | Erriapo | Siarnaq | S/2004 S 13 | Tarvos | Mundilfari | S/2004 S 17 | Narvi | S/2004 S 15 | S/2004 S 10 | Suttungr | S/2004 S 12 | S/2004 S 18 | S/2004 S 9 | S/2004 S 14 | S/2004 S 7 | Thrymr | S/2004 S 16 | Ymir | S/2004 S 8 see also: Rings of Saturn | Cassini-Huygens | Themis Retrieved from "http://en.wikipedia.org/"

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||