Bos sauveli (*)

Superregnum: Eukaryota

Cladus: Unikonta

Cladus: Opisthokonta

Cladus: Holozoa

Regnum: Animalia

Subregnum: Eumetazoa

Cladus: Bilateria

Cladus: Nephrozoa

Superphylum: Deuterostomia

Phylum: Chordata

Subphylum: Vertebrata

Infraphylum: Gnathostomata

Megaclassis: Osteichthyes

Cladus: Sarcopterygii

Cladus: Rhipidistia

Cladus: Tetrapodomorpha

Cladus: Eotetrapodiformes

Cladus: Elpistostegalia

Superclassis: Tetrapoda

Cladus: Reptiliomorpha

Cladus: Amniota

Cladus: Synapsida

Cladus: Eupelycosauria

Cladus: Sphenacodontia

Cladus: Sphenacodontoidea

Cladus: Therapsida

Cladus: Theriodontia

Cladus: Cynodontia

Cladus: Eucynodontia

Cladus: Probainognathia

Cladus: Prozostrodontia

Cladus: Mammaliaformes

Classis: Mammalia

Subclassis: Trechnotheria

Infraclassis: Zatheria

Supercohors: Theria

Cohors: Eutheria

Infraclassis: Placentalia

Cladus: Boreoeutheria

Superordo: Laurasiatheria

Cladus: Euungulata

Ordo: Artiodactyla

Cladus: Artiofabula

Cladus: Cetruminantia

Subordo: Ruminantia

Familia: Bovidae

Subfamilia: Bovinae

Genus: Bos

Subgenus: Bos (Novibos)

Species: Bos sauveli

Name

Bos sauveli Urbain, 1937

References

IUCN: Bos sauveli Urbain, 1937 (Critically Endangered)

Bos sauveli in Mammal Species of the World.

Wilson, Don E. & Reeder, DeeAnn M. (Editors) 2005. Mammal Species of the World – A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference. Third edition. ISBN 0-8018-8221-4.

Wilson, D.E. & Reeder, D.M. (eds.) 2005. Mammal Species of the World: a taxonomic and geographic reference. 3rd edition. The Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore. 2 volumes. 2142 pp. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. Reference page.

Vernacular names

Deutsch: Kouprey

English: Kouprey

español: Kouprey

magyar: Kouprey

日本語: コープレイ

ភាសាខ្មែរ: គោព្រៃ

polski: kuprej

português: Kouprey

ไทย: กูปรี, โคไพร

Türkçe: Kupro

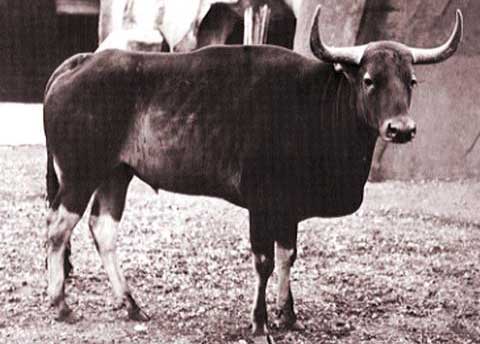

The kouprey (Bos sauveli), also known as the forest ox and grey ox, is a possibly extinct species of forest-dwelling wild bovine native to Southeast Asia. The name kouprey, derived from the Khmer language, means "forest ox".[5]

Known in Southeast Asia for thousands of years, the species was only described by Western science in 1937, when a specimen kept at the Parc Zoologique de Paris was described by the French zoologist Achille Urbain.[6]

The kouprey is listed as Critically Endangered, and possibly extinct, by the IUCN Red List,[7] with the last confirmed sighting of an individual taking place in 1969.[8]

Description

A bull (centre) and cow (right) kouprey, compared to a human.

Kouprey have a light and gracile build, in comparison to other wild cattle species. Both sexes have notched nostrils and their tails, noticeably longer than those of either gaur or banteng, measure between 3.3 and 3.6 ft. (100–110 cm) long.[9]

Calves are born a reddish bay colour, turning grey at around 5 months of age,[9] and the beginnings of horns appearing by 6 months old.[10] The pelage of cows and bulls diverges as they mature, with cows turning a mouse to brownish grey, while bulls become progressively darker, until individuals 12 years old or older are entirely dark brown. Both sexes have white stockings, with a dark strip down the front of each foreleg.[9]

Sexual dimorphism

Kouprey are a sexually dimorphic species and along with having different colour coats, males and females are distinguishable by the remarkably different shapes of their horns. Those of bulls are widely-set, similar to those of wild yaks, growing outwards before arching forwards and upwards, eventually fraying at the tips. While those of cows spiral upwards, growing into a shape reminiscent of a lyre. The horns of bulls can measure up to 32 inches (80 cm), and those of cows up to 16 inches (40 cm) long.[11]

Bull kouprey develop large dewlaps as they age, with those of mature individuals reaching lengths of 16 inches (40 cm) long. In some cases, the dewlap is so pronounced that it drags along the ground.[11]

Size

Kouprey are described as being intermediate in term of size between gaur and banteng, with adult animals measuring between 5.6 and 6.3 ft. (170–190 cm) tall at the shoulders, 7 to 7.3 ft. (210–220 cm) long from nose to rear, and weighing between 700 and 900 kg (1540–1980 lbs.).[11]

Distribution and habitat

The range of the kouprey once stretched from southeastern Thailand, southern Laos, down the western edge of Vietnam and centring in northern Cambodia,[12] though archaeological evidence shows the species could once be found as far north as Yunnan, China.[13]

The primary habitat of the kouprey is described as a mix of open grassland, along with dense and open canopy forests featuring grassy glades, waterholes and salt licks.[12]

Behaviour and ecology

Banteng in Alas Purwo National Park, Indonesia.

Kouprey behaviour is described as similar to that of the banteng, with the two species often being found grazing alongside each other, though not intermixing. Herds, made up of cows, their calves, and periodically bulls, are always lead by a mature cow.[9] Kouprey are active, if nervous, animals, being quick to flee if approached.[12] Bulls have been observed to plough up soil with their horns, especially around mineral licks and waterholes, which leads to the tips fraying.[9]

Feeding

To avoid the hottest parts of the day, kouprey feed during the early morning and late afternoon, moving into denser forest for respite during midday. Little information is available on the animal's diet, though various grasses and some browse, supplemented with mineral soil, have been recorded.[12]

Reproduction

Kouprey come together to mate during the month of April, with bulls dispersing back into bachelor herds by the beginning of May.[9] Gestation is between 8 and 9 months, with cows giving birth to a single calf between December and February. Female kouprey will isolate themselves to give birth, and remain away from the herd with their calf for the first month of its life. The total lifespan of a kouprey is thought to be around 20 years.[11]

Conservation

Threats

As with many large mammals, trophy hunting has likely been a considerable pressure on kouprey since their discovery by the Western world in the 1930s. War and political conflict, such as the Cambodian Civil War,[14] have also played a role in the species' decline through the destruction of habitat, poaching, and significantly disrupting conservation efforts and further study of the animal in the wild.[12]

Snares are a potential risk for any surviving kouprey,[15] with a 2020 report by the World Wildlife Fund estimating that over 12.2 million snares were present within protected areas in Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam.[16]

Conservation

Conservation efforts for the kouprey began in 1960 when Norodom Sihanouk, then head of state of Cambodia, gave the species protected status and created three natural reserves for it. These protected areas continued to be maintained by Norodom Sihanouk's successor, Lon Nol, but became neglected during the time of Khmer Rouge rule under Pol Pot.[17] During this period, the majority of the country's Forestry Bureau staff were killed, and all documents relating to the reserves were destroyed.[12]

Despite several expeditions by Dr. Charles H. Wharton to document kouprey during the 1950s, conservation efforts did not truly pick up again until the 1980s. When, on the 15th and 16th of January 1988, the University of Hanoi hosted the International Workshop on the Kouprey: Conservation Programme. Headed and coordinated by the IUCN, in a collaboration with the governments of Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam, and Thailand, with the aim of creating a feasible and realistic action plan for immediate kouprey conservation. Other organizations that attended and contributed to the action plan were the Association of Zoos and Aquariums, the Centre for Environmental Studies, VNIUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC), the Asian Wild Cattle Specialist Group, as well as WWF International.[12]

A 2011 examination by the IUCN of camera trap photos from northern Cambodia, some taken in known kouprey habitat, failed to turn up evidence of the animal.[8]

In late 2022, researchers from Re:wild and the Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research began a study to determine the status of kouprey in the wild. The goal of the study, through the examination of historical surveys and camera trap records, is to determine whether or not there is still suitable kouprey habitat that has yet to be searched.[15]

Population estimates

Kouprey are thought to have never been numerous as a species, likely never exceeding 2,000 individuals during the 20th Century.[14] In 1989, estimates put the total population of kouprey in Cambodia at less than 200 individuals, with between 40 and 100 surviving in Laos, and less than 30 in Vietnam.[12] As of 2016, the IUCN Red List puts the wild population at no more than 50 individuals, with a decreasing population trend.[7]

In captivity

Only two kouprey have ever been recorded in captivity. One, a young male, was captured in Preah Vihear Province, Cambodia, and sent to the Parc Zoologique de Paris by René Sauvel, a French veterinarian.[18] It arrived at the zoo in April, 1937, and was housed alongside a juvenile gaur and a juvenile water buffalo.[19] It died sometime during World War II.[20] Another calf was kept in a captive setting by Norodom Sihanouk during the 1950s, though details surrounding this individual are limited.[10]

Cultural signifance

Historically

A statue of two kouprey bulls, located in Mondulkiri Province, Cambodia.

Potential depictions of kouprey in rock art have been documented in the Cardamon Mountains of Cambodia,[21] and carvings in the temples of Angkor Wat have been found to resemble the animal as well.[20]

Kouprey have previously been hunted by locals for their meat, horns and skulls, the latter being highly symbolic culturally.[14]

Modern times

The kouprey is the national animal of Cambodia, being designated as such by Norodom Sihanouk in 1960,[18] its name is also the nickname of the country's national football team.

Several statues depicting and dedicated to the kouprey can be found across Cambodia, including in the country's capital city, Phnom Penh.[15]

During the 2022 Miss Grand Cambodia contest, model Pich Votey Saravody wore a costume depicting a kouprey, which stirred considerable controversy amongst viewers, many of whom felt the depiction disrespected the animal.[22]

Relation to other species

In 2006, research published by Northwestern University in London's Journal of Zoology indicated that a comparison of mitochondrial sequences showed the kouprey to be a hybrid between zebu and banteng.[23] However, the authors of the study eventually rescinded their conclusion.[24] A later study in 2021, based on a whole nuclear genome, found that the kouprey represented a distinct species, but formed a polytomy with the banteng and gaur due to incomplete lineage sorting, suggesting extensive hybridisation between their ancestors, resulting in the mitochondrial DNA of kouprey being nested within a group including a mixture of both banteng and gaur.[25]

References

K. Suraprasit, J.-J. Jaegar, Y. Chaimanee, O. Chavasseau, C. Yamee, P. Tian, and S. Panha (2016). "The Middle Pleistocene vertebrate fauna from Khok Sung (Nakhon Ratchasima, Thailand): biochronological and paleobiogeographical implications". ZooKeys (613): 1–157. doi:10.3897/zookeys.613.8309. PMC 5027644. PMID 27667928.

Timmins, R.J.; Burton, J. & Hedges, S. (2016). "Bos sauveli". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T2890A46363360. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-2.RLTS.T2890A46363360.en. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

"Appendices | CITES". cites.org. Retrieved 2022-01-14.

Grigson, C.: "Complex Cattle", New Scientist, August 4, 1988; p. 93f. URL retrieved 2011-01-27.

"Kouprey". www.wwf.org.kh. Retrieved 2023-06-21.

texte, Société zoologique de France Auteur du (1937-03-31). "Bulletin de la Société zoologique de France". Gallica. Retrieved 2023-06-21.

"Kouprey assessment". IUCN Red List. 14 May 2016.

Oon, Amanda (2022-09-19). "Politics of Extinction: On the trail of Cambodia's kouprey". Southeast Asia Globe. Retrieved 2023-06-21.

"The Wild Cattle of Cambodia | University of Nebraska Omaha". repository.unomaha.edu. Retrieved 2023-06-21.

Melletti, Mario (2014). Ecology, Evolution and Behaviour of Wild Cattle. Cambridge University Press. p. 233.

"Kouprey". ultimateungulate.com. Retrieved 2023-06-21.

MacKinnon, John Ramsay; Quy, Vo; Stuart, S. N. (1989). The kouprey : an action plan for its conservation. IUCN. ISBN 978-2-88032-972-3.

HOFFMANN, R. S (1986). "A new locality record for the kouprey from Viet-Nam, and an archaeological record from China". A new locality record for the kouprey from Viet-Nam, and an archaeological record from China. 50 (3): 391–395. ISSN 0025-1461.

"Kouprey". www.asianwildcattle.org. Retrieved 2023-06-21.

Joe, Coroneo-Seaman (2022-09-19). "The kouprey: on the trail of Cambodia's elusive wild cattle". China Dialogue. Retrieved 2023-06-21.

"Silence of the Snares: Southeast Asia's Snaring Crisis | Publications | WWF". World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 2023-06-21.

"War and conservation in Cambodia". Mongabay Environmental News. 2009-06-21. Retrieved 2023-06-21.

Hassanin, Alexandre; Ropiquet, Anne (2007-11-22). "Resolving a zoological mystery: the kouprey is a real species". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 274 (1627): 2849–2855. doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.0830. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 2288688. PMID 17848372.

Holmes, Branden. "Bos sauveli (Kouprey, Grey ox) – The Recently Extinct Plants and Animals Database". recentlyextinctspecies.com. Retrieved 2023-06-21.

Hausheer, Justine E. (2021-11-08). "Kouprey: The Ultimate Mystery Mammal". Cool Green Science. Retrieved 2023-06-21.

Latinis, David Kyle (April 2016). "The Kanam Rock Painting Site, Cambodia: Current Assessments": 10.

"Outrage as Miss Grand Cambodia appears in Kouprey costume – Khmer Times". 2022-09-12. Retrieved 2023-06-21.

"Northwestern biologists demote Southeast Asia's 'forest ox'". EurekAlert!. Retrieved 2023-06-21.

G. J. Galbreath, J. C. Mordacq, F. H. Weiler (2007) 'An evolutionary conundrum involving kouprey and banteng: A response from Galbreath, Mordacq and Weiler.' Journal of Zoology 271 (3), 253–254. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2007.00317.x

Sinding, Mikkel-Holger S.; Ciucani, Marta M.; Ramos-Madrigal, Jazmín; Carmagnini, Alberto; Rasmussen, Jacob Agerbo; Feng, Shaohong; Chen, Guangji; Vieira, Filipe G.; Mattiangeli, Valeria; Ganjoo, Rajinder K.; Larson, Greger; Sicheritz-Pontén, Thomas; Petersen, Bent; Frantz, Laurent; Gilbert, M. Thomas P. (November 2021). "Kouprey (Bos sauveli) genomes unveil polytomic origin of wild Asian Bos". iScience. 24 (11): 103226. Bibcode:2021iSci...24j3226S. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2021.103226. PMC 8531564. PMID 34712923.

Alexandre Hassanin, and Anne Ropiquet, 2007. Resolving a zoological mystery: the kouprey is a real species, Proc. R. Soc. B, doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.0830

G. J. Galbreath, J. C. Mordacq, F. H. Weiler, 2006. Genetically solving a zoological mystery: was the kouprey (Bos sauveli) a feral hybrid? Journal of Zoology 270 (4): 561–564.

Hassanin, A., and Ropiquet, A. 2004. Molecular phylogeny of the tribe Bovini (Bovidae, Bovinae) and the taxonomic status of the kouprey, Bos sauveli Urbain 1937. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 33(3):896–907.

Steve Hendrix: Quest for the Kouprey, International Wildlife Magazine, 25 (5) 1995, p. 20–23.

J.R. McKinnon/S.N. Stuart: The Kouprey – An action plan for its conservation. Gland, Switzerland 1989.

Steve Hendrix: The ultimate nowhere. Trekking through the Cambodian outback in search of the Kouprey, Chicago Tribune – 19 December 1999.

MacKinnon, J.R., S. N. Stuart. "The Kouprey: An Action Plan for its Conservation. "Hanoi University. 15 Jan. 1988. Web 13 Last Kouprey: Final Project to the Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund for Grant Number GA 10/0.8" Global Wildlife Conservation. Austin, TX, 25 Apr. 2011. Web 13 Nov. 2013.

Retrieved from "http://en.wikipedia.org/"

All text is available under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License